In First Timothy 1:8-11, Paul gives a striking list of the kind of people that the law was given in order to restrain: The law is not for the just, but

for the lawless and disobedient, for the ungodly and sinners, for the unholy and profane, for those who strike their fathers and mothers, for murderers, the sexually immoral, men who practice homosexuality, enslavers, liars, perjurers, and whatever else is contrary to sound doctrine…

What’s going on with this list? A list of vices is a conventional thing in the ancient world, but this one stands out for a few reasons. It’s uncharacteristic for Paul to launch into such a list in the opening sentences of a letter; he tends to save moral catalogues for the end of letters. But even odder is the sort of behavior Paul singles out here. After the general terms for wrongdoing, which are presented in three pairs (lawless & disobedient, ungodly & sinners, unholy & profane), Paul puts before our eyes matricides, patricides, murderers, two kinds of sexual sinners and two kinds of liars.

Some of these sins could be carried out in inconspicuous ways, but for the most part, these are dramatic, even melodramatic, sins. Taken together, “the general effect of the catalogue is to fill the reader with awe at the human capacity for vice,” notes the commentary by Jerome Quinn and and William Wacker (The First and Second Letters to Timothy: A New Translation with Notes and Commentary, Eerdmans, 2000).

Quinn and Wacker go on to ask, “Was there a setting in the ancient world within which one regularly encountered such vicious people as are listed here?” And in response, they make what I think is a fortunate guess:

Quinn and Wacker go on to ask, “Was there a setting in the ancient world within which one regularly encountered such vicious people as are listed here?” And in response, they make what I think is a fortunate guess:

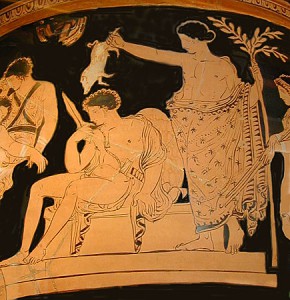

If one cast about for an adjective that would do justice to this catalogue, one could do worse than say that as a whole and in its parts it is dramatic. These evil people, larger than life, belong on the stage, and the ancient Greek drama, particularly the tragedy, was peopled with characters that illustrate why laws, human and divine, are laid down and why retribution overtakes them.

Quinn and Wacker then rifle through the ancient Athenian tragedians for examples of these behaviors, and for instances of this particular moral vocabulary. They are able to find them pretty easily, beginning with Aeschylus’ great Oresteia trilogy, filled “monstrous murder and matricide, which became the occasion for the Athenian legal system, under the aegis of the goddess Athena.” They also track them down in Sophocles and Euripides, where the same Greek terminology is found not just in the dialogue but in the words of the choruses. The only exceptions, they admit, are the words for sinners and the insubordinate, which were rare words, or words that came rather late into Greek vocabulary.

Especially through the choruses, the ancient playwrights commented on their horrific stories: “The tragedies themselves characterize one or another of the dramatis personae as lawless… or unholy… or profane.”

Of course the sinners in Paul’s list can be found elsewhere than in the classic Greek tragedies, and Quinn and Wacker admit there’s no proving that Paul had Aeschylus and company in mind when he made his striking list. But their comparison is an illuminating one, and allows the New Testament and Greek tragedy to throw mutual light on each other.