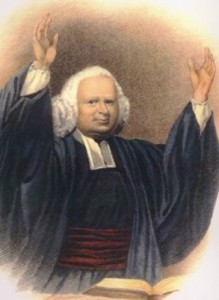

Today (December 16) is the birthday of George Whitefield (1714 – 1770).

Today (December 16) is the birthday of George Whitefield (1714 – 1770).

One of the best biographies of Whitefield called him The Divine Dramatist, estimating that he preached over 18,000 times over the course of more than 30 years in England, in Scotland, and in America. Whitefield was part of the original methodist awakening at Oxford. Though we no longer think of Calvinists like Whitefield as being “methodists,” he was part of that original Holy Club with the Wesleys, as one of the first Calvinistic Methodists (that is not a typo; there were such things). Whitefield seems to have taken the lead in carrying out a preaching ministry that was aggressive. He preached anywhere and everywhere.

Whitefield was an international celebrity, and eighteenth-century figures famous for their coldness toward religion bear witness to the power of his oratory. David Hume, for instance, was struck by a Whitefield sermon in which he called on the angel Gabriel to linger on earth a while longer to hear news of a sinner repenting. Ben Franklin found himself talked into giving money to charitable causes by a Whitefield sermon, though he had pledged not to part with any of his cash that day. An actor said he would give a large amount of money if he could only say the word “Oh” like Whitefield could; and another man said that Whitefield could move a crowd to tears just by the way he pronounce “Mesopotamia.”

But for a more substantive assessment of Whitefield’s preaching, we turn to a fellow believer, and a fellow evangelical, a fellow Anglican, and a fellow Calvinist: J.C. Ryle (1816-1900). In his short book on Whitefield, Ryle gives six characteristics of Whitefield’s preaching:

1. A Pure Gospel.

First and foremost, you must remember Whitefield preached a singularly pure gospel. Few men ever gave their hearers so much wheat and so little chaff. He did not get into his pulpit to talk about his party, his cause, his interest, or his office. He was perpetually telling you about your sins, your heart, and Jesus Christ, in the way that the Bible speaks of them. “Oh, the righteousness of Jesus Christ,” he would frequently say; “I must bo excused if I mention it in almost all my sermons!” This, you may be sure, is the corner stone of all preaching that God honors. It must be preeminently a manifestation of truth.”

2. Clarity and Simplicity.

For another thing, Whitefield’s preaching was singularly lucid and simple. You might not like his doctrine, perhaps, but at any rate you could not fail to understand what he meant. His style was easy, plain, and conversational. He seemed to abhor long and involved sentences. He always saw his mark and went direct at it. He seldom or never troubled his hearers with long arguments and intricate reasonings. Simple Bible statements, pertinent anecdotes, and apt illustrations were the more common weapons that he used. The consequence was that his hearers always understood him. He never shot above their heads. Never did man seem to enter so thoroughly into the wisdom of Archbishop Usher’s saying, “To make easy things seem hard is easy, but to make hard things easy is the office of a great preacher.”

3. Boldness and Directness

For another thing Whitefield was a singularly bold and direct preacher. He never used that indefinite expression, “we,” which seems so peculiar to English pulpit oratory, and which leaves a hearer’s mind in a state of misty confusion as to the preacher’s meaning. He met men face to face like one who had a message from God to them –like an ambassador with tidings from heaven. “I have come here to speak to you about your soul.” He never minced matters and beat about the bush in attacking prevailing sins. His great object seemed to be to discover the dangers his hearers were most liable to, and then fire right at their hearts. The result was that hundreds of his hearers used always to think that the sermons were specially addressed to themselves. He was not content, like many, with sticking on a tailpiece of application at the end of a long discourse. A constant vein of application ran through all his sermons. “This is for you; this is for you; and this is for you.” His hearers were never let alone. Nothing, however, was more striking than his direct appeals to all classes of his congregation as he drew towards a conclusion. With all the fault of his printed sermons, the conclusions of some of them are to my mind the most stirring and heart-searching addresses to souls that are to be found in the English language.

4. Earnestness.

Another striking feature in Whitefield’s preaching was his thundering earnestness. One poor, uneducated man said of him that he preached like a lion. Never perhaps did any preacher so thoroughly succeed in showing people that he, at least, believed all he was saying, and that his whole heart and soul and strength were bent on making them believe it, too. No man could say that his sermons were like the morning and evening gun at Portsmouth, a formal discharge, fired off as a matter of course, that disturbs no body. They were all life; They were all fire. There was no getting away from under them. Sleep was next to impossible. You must listen whether you liked it or not. There was a holy violence about him. Your attention was taken by storm. You were fairly carried off your legs by his energy before you had time to consider what you would do. An American gentleman once went to hear him for the first time in consequence of the report he heard of his preaching powers. The day was rainy, the congregation comparatively thin, and the beginning of the sermon rather heavy. Our American friend began to say to himself, “This man is no great wonder, after all.” He looked round and saw the congregation as little interested as himself. One old man in front of the pulpit had fallen asleep. But all at once, Whitefield stopped short. His countenance changed. And then he suddenly broke forth in an altered tone, “If I had come to speak to you in my own name, you might well rest your elbows on your knees, and your heads on your hands, and sleep; and once in a while look up and say, ‘What is this babbler talking of?’ But I have not come to you in my own name. No, I have come to you in the name of the Lord of Hosts! (here he brought down his hand and foot with a force that made the building ring) and I must and will be heard!” The congregation started. The old man woke up at once. “Ay, ay!” cried Whitefield, fixing his eyes on him, “I have waked you up, have I? I meant to do it. I am not come here to preach to stocks and stones. I have come to you in the name of the Lord God of Hosts and I must and will have an audience.” The hearers were stripped of their apathy at once. Every word of the sermon was attended to. And the American gentleman never forgot it.

5. Power of Description

Another striking feature in Whitefield’s preaching was his singular power of description. The Arabians have a proverb which says, “He is the best orator who can turn men’s ears into eyes.” If ever there was a speaker who succeeded in doing this, it was Whitefield. He drew such vivid pictures of the things he was dwelling upon that his hearers could believe they actually saw them all with their own eyes and heard them with their own ears. “On one occasion,” says one of his biographers, “Lord Chesterfield was among his hearers. The preacher, in describing the miserable condition of a poor benighted sinner, illustrated the subject by describing a blind beggar. The night was dark, the road dangerous and full of snares. The poor sightless mendicant is deserted by his dog near the edge of a precipice and has nothing to grope his way with but his staff. But Whitefield so warmed with his subject and unfolded it with such graphic power that the whole auditory was kept in breathless silence over the movements of the poor old man, and at length when the beggar was about to take that fatal step which would have hurled him down the precipice to certain destruction, Lord Chesterfield actually made a rush forward to save him, exclaiming aloud, “He is gone, he is gone!” The noble lord had been so entirely carried away by the preacher that he forgot the whole was a picture.

6. Feeling

One more feature in Whitefield’s preaching deserves especial notice, and that is the immense amount of pathos and feeling which it always contained. It was no uncommon thing with him to weep profusely in the pulpit. Cornelius Winter goes so far as to say that he hardly ever knew him get through a sermon without tears. There seems to have been nothing whatever of affectation in this. He felt intensely for the souls before him and his feeling found a vent in tears. Of all the ingredients of his preaching, nothing I suspect, was so powerful as this. It awakened sympathies and touched secret springs in men which no amount of intellect could have moved. It melted down the prejudices which many had conceived against him. They could not hate the man who wept so much over their souls. They were often so affected as to shed floods of tears themselves. “I came to hear you,” said one man, “intending to break your head, but your sermon got the better of me: It broke my heart.” Once become satisfied that a man loves you, and you will listen gladly to any thing he has got to say. And this was just one grand secret of Whitefield’s success.