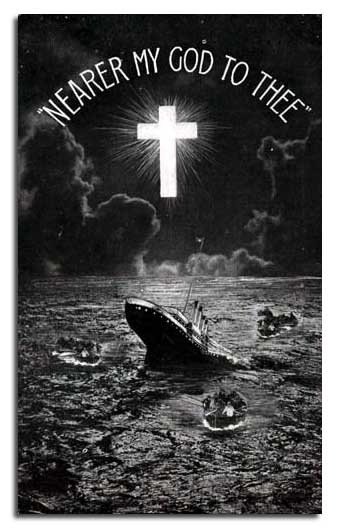

On April 14, 1912, the Titanic struck an iceberg. In the early hours of the next morning the great ship sank, and everybody was talking about it. Pastors were talking about it. One pastor, in Safenwil, Switzerland, said to his congregation, “I would like to encourage you to reflect on it.” He was the 26-year old Karl Barth. Eventually The Princeton Seminary Bulletin published a translation of that sermon from Sunday, April 21, 1912 (Vol. 28 No. 2 (2007)), and it has since been reprinted in a very short book with another of Barth’s early sermons.

On April 14, 1912, the Titanic struck an iceberg. In the early hours of the next morning the great ship sank, and everybody was talking about it. Pastors were talking about it. One pastor, in Safenwil, Switzerland, said to his congregation, “I would like to encourage you to reflect on it.” He was the 26-year old Karl Barth. Eventually The Princeton Seminary Bulletin published a translation of that sermon from Sunday, April 21, 1912 (Vol. 28 No. 2 (2007)), and it has since been reprinted in a very short book with another of Barth’s early sermons.

Karl Barth in 1912 is “Barth before he was Barth,” in most ways. He was still fresh from seminary, just out of a curacy and settling into his first solo pastorate. He wouldn’t be married until the next year. His epochal Romans commentary was still seven years in his future, never mind the great Church Dogmatics which he would produce over the decades before his death in 1968. But back in the second year of his pastorate, he was doing his best to preach the unpreachable liberal theology he had learned in seminary, and had not yet discovered for himself just how useless the modernized gospel was at comforting modern man. He was trying to love his parishioners the best he could, mainly by getting involved in their social and economic conflicts as “the red pastor of Safenwil.”

Looking back on these early days, Barth later remarked with some regret, “During my time as a pastor… I often succumbed to the danger of attempting to get alongside the congregation in the wrong way. Thus in 1912, when the sinking of the Titanic shook the whole world, I felt that I had to make this disaster my main theme the following Sunday, which led to a monstrous sermon on the same scale.” (from the definitive Barth biogarphy by Eberhard Busch, p. 63) Yes, Barth took as his sermon text the current event of a disaster, rather than an actual portion of Scripture. He tacked on a bit of Psalm 103 (“as for man, his days are like grass”) at the beginning, but this sermon was clearly about the boat, and Barth was not leading his congregation into the word of God, but into the world of current events. “Do not stop short at my words, then, but consider for yourselves what God wished to say to us through this.” Yes, apparently God was speaking in this disaster, and Barth thought his job as a preacher was to interpret the “word of God” in the Titanic disaster, rather than the word of God in Holy Scripture. “Later, I was sorry for everything that my congregation had to put up with.” (Busch, p. 64)

What does the young, liberal-trained Karl Barth have to say about this message from God in the sinking of the Titanic? First, he (Barth, not God, presumably) is astonished by the scope of the ship, calling it “a miracle of the modern human mind, which utterly surpasses even the most fantastical images any of us could conjure up…” Were its makers sinning in constructing such an astonishing thing? No, says Barth: “The simple-minded will draw the conclusion that it is a sin to build ships this big and to journey across the sea in them. Quite the reverse, I am saying. It is entirely God’s will that the world’s technology and machinery attain to higher degrees of perfection. For technology is nothing other than mastery over nature, it is labour, and the divine spirit in humanity ought to expand in this labour and to prosper.”

Nevertheless, there is something wrong with the Titanic; not its status as an engineering feat per se, but the ostentatiousness of it: the fact that it was a floating shopping mall with swimming pools and a well-stocked fishing pond, fine cuisine and every luxury. “There is a way of using technology,” Barth warns, “that cannot be called labour any more, but playful arrogance. It is arrogance to install theatres and fish-pools on a vessel exposed to these sort of risks…” Building amazing boats is one thing, but the Titanic was just goofy: “God will not be mocked. He certainly intends us to work and to achieve something in the world. But he does not intend us to act as though we were done with working, and could now go fooling around.” Such lack of seriousness calls forth the judgment of God, and the sinking of the Titanic is apparently to be understood as God’s judgment.

As a result, the executives of the company behind the Titanic now have “1500 dead people on their consciences.” But the responsibility extends further, to the whole economic system that the Titanic represents: “But ultimately not even this shipping company bears all the guilt for this disaster, but first and foremost he system of acquisition by which thousands of companies like this one are getting rich today, not only through shipping but across the whole spectrum of human labour.”

Barth, soon to be known as “the red pastor of Safenwil” for his support of communistic solutions to the exploitation of factory workers in his town, leans into his role as prophet announcing God’s wrath against capitalism: “As long as self-interest is not now eradicated and replaced by the idea of one-for-all and all-for-one, as long as we do not now repent and strive for a truly communal labour, we run the risk of conjuring down upon ourselves calamities of a quite different sort than the sinking of the Titanic.”

But not all is gloom and doom in this outpouring of divine wrath. Barth is encouraged by the stories of heroic conduct. He sees in them a sign that the kingdom of Christ is extending its influence in the hearts of men: “One senses something of how Christ is becoming an ever greater force in the world, when one reads of those who did not seek to save themselves but for others, who silently and nobly retreated in the face of death to allow those who were weaker than themselves to continue on the path of life.” The heroism of some on the Titanic is certainly worthy of admiration, but it is hard to see it as confirmation that “Christ is becoming an ever greater force in the world” unless you were already inclined to find that kind of optimistic eschatology before you read the morning news.

Barth’s seminary trained him in classically liberal Christianity. He entered the pulpit with a set of beliefs that were brittle, insufficiently biblical, and ultimately irrelevant to real people. In the Titanic sermon, you can see him trying to make his liberalism stretch to cover currrent catastrophes. It stretched enough to cover the Titanic, but just barely. This sermon was a real stinker, a real sinker, and it went under pretty fast. But Barth’s preaching career kept going until a few years later when the outbreak of World War I would be an even more titanic challenge to the weak Christianity of his seminary training. When that happened, Barth couldn’t stretch the thin commitments of liberalism to fit the real world.

That’s when he stopped preaching headlines, stopped trying to declare which economic system God hates or what God was up to in the latest disaster, and started preaching from what he called “the strange, new world of the Bible.” And that’s when he found that he had something to say which the world didn’t already know.

Update: Ben Myers at Faith & Theology puts in a good word for Barth’s Titanic sermon, calling it “an extraordinarily gripping and powerful piece of preaching.” As you can tell from this post, I find myself more in agreement with Barth’s own later regret over this “monstrous” piece of preaching. But give Myers’ post a read.